Talking Insider Threat Awareness with Bill Evanina

Share

Podcast

About This Episode

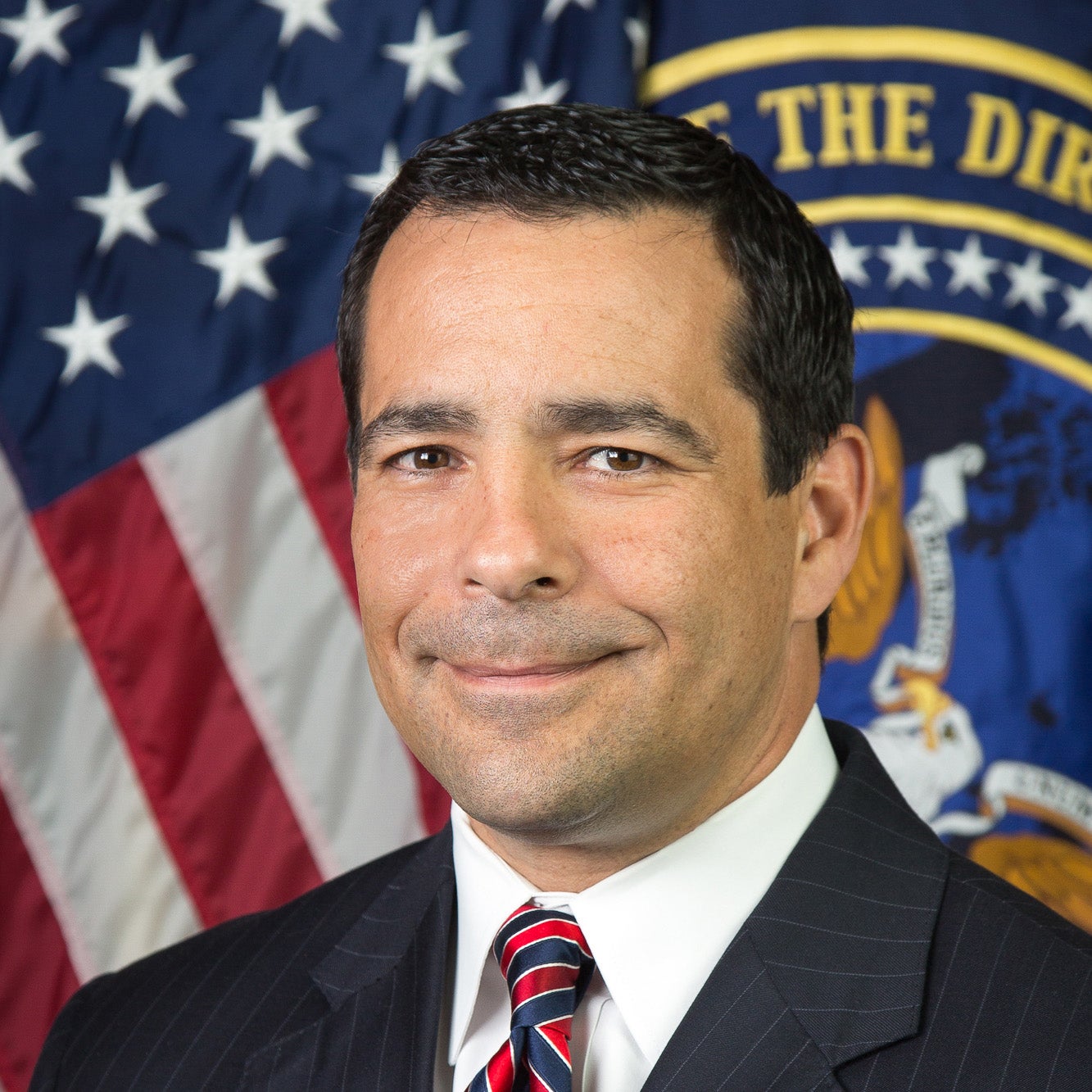

Bill Evanina, Founder and CEO of the Evanina Group and former Director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, joins the podcast this week to take a deep dive view into an insider threat as September is Insider Threat Awareness Month.

He shares insights from his many years on the counterintelligence and security front lines on what defines insider threat (Note: harm to self or others), the opportunities and challenges in available tools, information sharing and detection across organizations, the importance of leadership training and cross-functional partnership to help mitigate insider threats and the criticality of sharing success stories (these really make a difference)!

Podcast

Popular Episodes

50 mins

REPLAY: Someone Needs to Do Something, But Who?

Episode 278

March 26, 2024

47 mins

Cyberwar, Social Media’s Future and Passing the Mic with Peter W. Singer

Episode 206

November 8, 2022

56 mins

The Conga Line of Cybersecurity in 2022 with Manny Rivelo

Episode 167

January 25, 2022

48 mins

See Something, Do Something: A Conversation with Dmitri Alperovitch

Episode 160

November 30, 2021

Podcast

Talking Insider Threat Awareness with Bill Evanina

[01:40] On the Front Lines of Insider Threat

Rachael: We've got Bill Evanina, the founder and CEO of the Evanina Group. He’s a former director of the National Counter-Intelligence and Security Center, in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Bill: It's a pleasure to be here. I'm very humbled to be a part of your podcast and look forward to our very robust discussion.

Rachael: Bill, you've had such an amazing career. You've been on the front lines of, I think some of the most fascinating, intriguing, and horrifying things in the last several decades. Now you're doing your own thing too. I'm so excited that you're on the podcast to share with us your insights because, for those that don't know, you were in the FBI for 24 years. You've gone on and been encountering intelligence for decades.

Just thank you for your service, I guess that is what I'm trying to get at. Thank you very much, because it's not easy. September is National Insider Threat Awareness month. Bill, for the benefit of our listeners, could you share a little bit more about that?

Bill: Thanks for recognizing the fact that September is National Insider Threat Awareness month. Every month has an awareness of something, and some months more than others have plenty of them. In my time, both at the FBI, and CIA and most specifically my time as director of NCSE, this was our big month of the year. If you are in the security, counterintelligence business, or counter-terrorism business, the insider threat month is the pinnacle of all the months of themes.

Damage Caused By an Insider Threat

Bill: As much as we want to look at threats to people, data systems, and countries, along the gamut of cyber, and ransomware, nothing compares to the threat and damage caused by an insider threat. It's above and beyond anything, it always has been, always will be. I think it's got misplaced over the years, in terms of what it means. But, for me personally, this was always the big month. We always probably would have 40 or 50 events in a 29-day month.

Eric: We spend so much time talking about cyber security. We spend so much money on cyber security. When you say that insider threat is the bigger cost to our nation, society, and nations, why do you think we can't get that traction around insider threat? I mean we have sensationalized cases. We've got Aldrich Ames, we've got Snowden. You can go back to the atomic bomb during, and after World War II. There are some really juicy, I hate to even use the word, but there are some stories that people can relate to. Why do you think that is?

Bill: Well, here are hundreds of stories. If you just go on the DoD website and look at economic espionage, you mentioned the government ones, the private sector probably has 10x of those. But they're sometimes not all classified in the vernacular of insider threats.

The phrase, insider threat, has a connotation for different people. It could be the Hanson and the Ames, the individuals in the last decade, Wikileaks, there's a whole bunch. Or there could be the Aaron Alexis's, the Fort Hoods, the Pensacola's, terrorists.

Failing at the Marketing of What an Insider Threat Is

Bill: At the end of the day, we failed at the marketing of what an insider threat is. We were so worried about the mitigation capabilities, the UAM, the training, the privileged users, and the removable hard drives. We've lost the feel for the marketing of what are we trying to prevent. What I've been using since 2012, it's corny, but it works for me, is that individual who tomorrow will come to your workplace to do bad things.

Those bad things could be a bomb in the cafeteria, it could be shooting, a suicide, a murder-suicide, or a thumb drive. It could be downloaded on purpose, clicking a link, the whole gamut. But again, at the end of the day, it's about a human being. It's the human dynamics, social behavior, keyboard behavior, and the ability, or inability of the government, or company to prevent that person from doing bad things that they're bound to do.

All the insider threat vernacular has been in response to an event. Then again, from a guy who I think, in preparation for this, I have 36 congressional hearings just on insider threat, from three different agencies, and you run the gamut. Every single one of them has been a different rabbit hole, a different lane, and a highway, but missing the umbrella aspect of a human being.

We'll talk more about where we still lack in a lot of it, but we've been so focused on the behavioral analytics of things that people do, and not on what's in their heads. There's a rationale for that.

The Lack of Leadership in the Government

Bill: To Rachael's point, my business now in the last couple of years, which I'm predicated in the board of director space and the CEO space, I found that to be somewhat true. But they're more willing to make a decision to say, "We can mitigate this by doing A, B, and C, and it's just going to cost me X." They do it. That's the lack of leadership we've had in the government for decades.

Eric: There are so many good examples and we still can't pull it together. I love your definition, I think it's very simple and relatable, and I think we have a real problem here.

Bill: I think from the definition of preventing that individual from coming in tomorrow and doing bad things. 80% of that can be done with behavioral analytics in the workplace, from where you log into your building, your cat card, or all the way up to your first keystroke.

Where you log in, what websites you go to, any kind of deviation, standard deviation from the norm of your BI behavior at work that's 80% percent of it.

The most damaging 20% is what we have no capability of uncovering, is what's the state of your mind? I think that's the part we're missing, but that is also the part that the private sector is more than willing to get to the behavioral analytics in your mind, and what your thought process is. There are all kinds of cool capabilities out there on retinal capability, and that's the space that the government has never wanted to go down that road.

[08:15] The Insider Threat Space

Eric: Rachael, could you imagine private industry trying to read my mind and what they'd find? We could break a company with that exercise. If I was a POC, a proof of concept.

Bill: Let me just give you just an anecdote, because your listeners are probably thinking, "What is he talking about?" For instance, in the insider threat space in the federal government. We'll stay in the intelligence community, the Department of Defense, where they have the highest levels of capabilities, and success rates. There is no connectivity to an employee, supervisory relationship, and feedback, that connects to the security apparatus of that agency.

Eric: Let's make sure we understand this. So, I report to a manager, my manager does employee evaluation reports, you name it on me. I make a mistake. They may counsel me, and put it in my HR record. You're saying there is no connection between that and the insider threat team. In my security firm. Seriously?

Bill: Unless that supervisor makes an affirmative move to wake up one day and say, "I think Eric might be a security risk to our company. I'm going to go find out who I report this to." And he does it. If that's not the case, there is no business process for that to happen in the government, or even in the intelligence community.

We tried to make this in 2018, and beyond. Part of the process was when we did Trusted Workforce 2.0, and we were disallowed by the GS-14 and 15 attorneys who say, "No, it's a violation of privacy. You need to keep HR separate from security." That's the baseline of, I'd say our failures over time in the government, not including human resources.

Trusted Workforce 2.0

Bill: As part of our Trusted Workforce 2.0 program, we worked in partnership with the Brits, the Canadians, and Australians to look at key indicators of why people and employees go bad. Often than not, all five of the Five Eye countries came up with, they were all over the map. The one key indicator was that an employee, who over an 18-month period did not get promoted two or more times, was often than not the primary indicator, or predicate for that person going bad. There's not a security organization in the world that gets that data.

Eric: I'm blown away having a security clearance, just the financial disclosure paperwork. I don't think you've ever seen it, but the amount of data you have to put in, and listing out things like art. All of your financial records, and the likelihood that you forget something is super high, by the way, because you forget a lot.

I forgot two stepbrothers on my disclosure, my SF-86 at one point too, which they reminded me of. But that's a different story. But the amount of disclosure is incredible, and they don't even look at something that the organization owns. I mean, the organization owns my employee evaluation form.

The feedback is owned by the organization, my financial data isn't. Where I'm spending money, what I'm spending it on, what I'm doing isn't. You would think that would be the bigger privacy risk.

Bill: No, the federal government, and I'll say the federal government, particularly in the intelligent community, Department of Defense. It's even a bigger issue in the non-Title 50 organizations, that sanctity of employee boss relationship is almost unbreakable.

The Big Five That Are Really Into an Insider Threat

Bill: So, where you have in the big three agencies, the big five that are really into insider threat, you have a hub where you'll have a representative from human resources in the insider threat hub. But there's not a data stream, where you could have AI built against that, or you could have analysts looking to say, "Well, you know what? Eric, for 10 years, was getting fives across his portfolio. In the last three years, he's gotten a four, and two threes in this past year.

Now he's on a performance improvement plan." That's a key indicator of something going awry, and that does not get sent to security teams or apparatus.

Eric: Are you reading my employee reviews, by the way? Those are pretty accurate.

Bill: Just trawling the internet, Eric.

Eric: That is bizarre.

Rachael: It's fascinating, the gaps that you find, that just kind of don't seem to make sense. So, how do you address that? How do you try to start making connections?

Bill: It's a marketing issue. To me, it has been, if you look at, what are we trying to achieve here? If you just step back. You're trying to achieve identifying potential bad actors, in any space. That becomes a human resources issue. You're trying to help individuals who are needing help.

It becomes a tool for the human resources ecosystem, but they won't, for the most part, won't let you in that ecosystem. At the end of the day, they look at it as, "We're trying to catch a spy, or stop a terrorist, or prevent a shooting." To me, it's much more than that.

Robust Insider Threat Program

Bill: It's an enabling factor to help employees who might need employee assistance programs, and who are searching out and begging for help. This program could really be that cursor. When you see success stories, reports of identification of bad actors, or potential suicides prevented, that's because they have a robust insider threat program available to them.

That also is masked, but because it's part of a human resources program. I think that's the bigger picture. If you're trying to protect employees, their surroundings, and other employees, that's the right marketing space, but the security folks don't tend to do that. It's really bifurcating the government from security is way over here, and HR is way over there.

Eric: So if I'm reporting to Rachael, and she's looking at me and saying, "Hey, you're off Eric, but you're really off today, or this week, or I've noticed a change in pattern." What you're saying is, from an insider threat perspective, if we're in the government, they may detect my behavior change using systems that exist. But, there's really nowhere to go, in most cases, for Rachel, as my manager, if she detects abnormal behavior.

Bill: That's correct. Two aspects of this that I think are germane to our conversation. Number one, there is no formalized process for Rachael to click a button and say, "Not only do I see a change in Eric's workload and productivity, but he just looks disheveled. He's coming in late. He never used to come in late. The office scuttlebutt is that maybe his wife might have left him, or his kid has a special need. There's no place for Rachael to even report all that, number one.

Bucket of Potential Harm

Bill: Number two is Rachael's not qualified to evaluate all those things and put him in the bucket of potential harm.

Eric: She's not qualified. You're absolutely right.

Bill: My argument is if she gave that information to a security apparatus, they're more qualified to seek key indicators. Then check other parts of your portfolio to say, "Oh yes, you know what? We see here, that he's in bankruptcy. He filed for bankruptcy. That's a problem."

Rachael might not know that, because she's your boss.

Eric: The systems aren't linked, either.

Bill: They're not linked, and they clearly need to be linked, but also, who has the ability, and this is my argument here is, we don't need sophisticated AI. It might help, but we just need someone to have eyes on, looking at Eric's portfolio. Then when you add in Rachel's assessment, you're like, "Wow, let's get in front of Eric. Let's get him some EAP help, a counselor, a defensive brief, and wait a minute. Do we just see here that in the last six months he traveled overseas four times, but only reported it once?"

Then wait, he's got two skiff violations, that are in this other file. It's the aggregate of all that data that has the best ability to identify risk in person, a totality of the risk of Eric, and we're not doing the best job of that.

Eric: Rachel, how do you feel about that? They want to look at everything about you.

Rachael: Well, I'll say I'm in favor because you look at the stress that COVID put literally on everybody in the world today, the society of being on lockdown.

[16:29] The Business Aspects of Insider Threat

Rachael: I think if you look around, a lot of people are still struggling. There are people in my personal sphere, who sometimes want someone to approach them. Notice what's going on, versus being the person to say, "I'm not okay." Sometimes I think that could be helpful in a lot of ways, for a lot of people out there, even just generally, in addition to the business aspects.

Bill: Here's the Conner narrative for you. Let's play this out. You do see some lack of productivity, and change in Eric, the way he dresses, the way he looks, what time he's coming in. He's just not been effective, and you report it to security. What's your response? Now, his reporting period is up in October, and he gets another lower rating, right now he's filed an EEO grievance against you.

Rachael: 100%, yes.

Bill: That is the circle of where I would say, and I say this all the time, that's where the GS-14 and 15 government attorneys get involved. They say, "We don't want to go down this road."

Rachael: It's a slippery slope.

Bill: It's an immediate slope, and it's guaranteed to be there.

Eric: But if we don't go down this slope, give us a good story. We don't need names necessarily, although they do make it juicy. Give us an example where, if we had gone down this slope, we could have avoided tragedy. We could have avoided grave harm to the United States of America. Give us an example, because we didn't go down there, we're in trouble. I'm sure you have hundreds.

Working With the US Government in the Five Eyes

Bill: We don't have time to give you all these examples in my mind, but I'll give you just a few scenarios. In our Trusted Workforce, 2.0 construction, and working with the US government in the Five Eyes. We never saw a scenario where after the fact, the supervisor didn't say, "I saw all these indicators, you should have just asked me." So, that's never happened.

Eric: I just want to translate. The supervisor, in this case, sees that I'm off. She sees the indicators, and she has nowhere to go. But in every example, you're talking about, the supervisors know.

Bill: Where it gets even more complicated is, that you report to Rachael, but you're a contractor. So not only is Rachael seeing this, but you're contractor supervisor. A program manager is seeing you right being off as well. So you have two managers seeing Eric awry. Then

Eric goes and does something bad. You have two supervisors in the chain of command saying, "Well, geez. We saw this in Eric for the last six months. If somebody would have asked me, I would've told him that Eric was looking at this space."

You can go back to Aaron Alexis, and the Navy Yard, the biggest case there, where multiple supervisors had identified him as a problem. Or you go to Snowden, you go to Manning, all the big-name ones. Then you go to the latest case with the CIA officer, they're a dime a dozen, all these situations. You go back to Hansen and Ames, the supervisors are like, "Nobody asked me, but I would've told you, they both had drinking problems, financial problems, all the key indicators."

Awesome and Effective Tools for Insider Threat

Bill: But where this is more germane to me, my time now in the private sector, it's that story times 100 in the private sector. They are where the government was in 2011 when it comes to insider threat because they hear that, they think, "Corporate espionage. Someone's stealing my IP to sell to China, or to Coca-Cola." But it's more than that. But the difference is, that they're more willing to use awesome, and effective tools to combat this, whereas the government is not.

Eric: My experience actually is, they don't think of it from an industrial. Historically, going back five, or 10 years, the commercial industry hasn't looked at IP theft. We've been really good at transferring it to China, transferring it to other nations, and they don't think of it that way. I've worked with customers, and my teams have worked with customers where we've said, "You have a problem." Research data around medical research. Well, you have a China problem.

Who's got the biggest cancer problem in the world? China. Who's interested in your information? We're seeing it right here, and they don't think that way in many cases.

Bill: No. Two things here, just imagine the Rachel scenario we just went through as your boss. In the UK and Australia, they go one step further. They go to your peers. Could you imagine the US, and a government agency, the ability of your peer to report you?

Rachael: No.

Bill: That's the mindset. On top of that, the Australians, and the Brits have a great program called the ASA. We tried to adopt this in 2019, and we failed miserably, but, it's called the annual supervisory assessment.

Reevaluation of Security Clearance

Bill: Instead of getting this done every five years on a reevaluation of your security clearance, it happens every year. When a supervisor gets 10 questions about your makeup, and your change and that supervisor gets the do a 10-question multiple-choice thing, and that goes to the security folks. Separate, and distinct from your annual performance, because it's done on your birthday, so it's just about you. It's the same 10 questions you get on a periodic investigation.

We could not get that through because of the privacy and civil liberty attorneys.

Eric: Nobody wants bad news on their birthday.

Bill: Nobody wants any kind of information. The Australians and the Brits will tell you, it's their number one key indicator of risk, is that supervisory assessment.

Eric: I'm just thinking through that, that makes me uncomfortable thinking about it. If I had to rank my employees, and do I have any that show any signs, I could be in a very difficult, challenging position there.

Bill: Now, take it one step further. The argument, my aspect is, that you shouldn't be alone in that position to make those judgments on your own, without viable training. There needs to be viable, comprehensive training for Rachel and Eric, to be able to say, "Here are the key indicators. Here's what to look out for. Let's not go crazy here."

But while understanding, when you click that button to submit a concern, there are ramifications, and hold harmless when it comes to performance evaluation and EEO issues. It's complicated.

Rachael: They follow you around.

Eric: But it is almost similar to the questioning you get if somebody puts you down on their security application, the SF-86 as a neighbor, or a reference, or an employer.

Strange Times of Day with Insider Threat

Eric: We will have an investigator come in, and talk to you. They'll ask you questions. I don't want to go into the questions, but does everything appear normal? Have you seen any odd behaviors? Things like, we had strange times of day, strange people. They will ask questions, and if you modify those questions for a supervisor or a peer group, that's probably comparable.

Bill: It's the same thing. We decided to not do every five years, but to do it every year. We've got great data. Australians and Brits do it very successfully. If the Australian government, which is smaller scale wise could say, "It's the number one key indicator of risk." We should at least pilot the program, which we did.

We’ve had successful pilots, and we continue to do that. But at the end of the day, our government, and our culture, this is all about culture. Our privacy and civil liberties are still superseding the need for a secure workplace. COVID made that times 10.

Eric: We've seen a number of examples lately. The Navy Yard, we've seen Pensacola, where a non-secure workplace, or a workplace where we just didn't catch somebody, who had obviously issues, has resulted in grave harm to people we care about.

Bill: If you look at Pensacola, same church, different pew. But if the government and the security apparatus were able to identify, or look at social media, you could have identified, and prevented that before it happened. But we're not able to do that because we live in the greatest democracy ever. Law enforcement, or security, can't search our social media. But if we could have, we could have prevented that.

[24:06] Different Layers of an Insider Threat

Bill: So there are different layers to this, and how far will we be willing to go? But my argument is if you have a top-secret clearance, or you have a security clearance, you've waived all your rights.

Eric: Well, that's my perspective.

Bill: I agree, but that's not the perspective of the majority of the GS-14 to 15 attorneys in the US government.

Eric: In fact, you literally waive your rights when you sign the paperwork.

Bill: When you come to work, and you log on, and the banner's right there, the banner is the banner. Everything you type is now the ownership, for monitoring 24/7, but still, you have attorneys, and DoD, as we know, is still resisting a lot of that. But at the end of the day, we find ourselves in a place where we have event after event and then going back to say, "Well, why didn't we fix this in 2010, and 11, and 15, and 16, and 18?"

Because we all have great policies. Even in my old shop, we would write policies on security clearance reform. We would issue the policy, but it was up to the individual agencies to adopt that policy. There was no mandate. Reciprocity becomes an issue, and then what you end up happening is, that you have a bad actor who works for a company. The host agency says, "You know what? We don't like Eric. Eric just isn't fit for our culture, and he's had three security violations." Send it back to his company, and this company that puts them on another contract, at another agency.

How Do We Contain the Badness?

Bill: That's the whole construct of, other people that we could talk about in this space, that have gone bad, and then the containment becomes the answer. How do we contain the badness? We can contain, or we can deal with national secrets that have been lost, but you can't contain the loss of human life. If we have viable solutions to prevent that, then it's on us. We should be held accountable for not employing those solutions.

Eric: Now, when it works, though, we do save lives. We do save critical intellectual property. I don't remember, you probably know, Bill, the Coast Guard incident with Lieutenant Hassan.

Bill: Worked perfectly.

Eric: Somehow the Coast Guard was able to stop him. I just remember vividly from the front page of the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and the New York Times. The arsenal that federal investigators pulled out of, I think it was his house. It might have been a storage container or something. The thoughts that went through my head were like, "This would've been a massive tragedy." He was stopped. There's also proof that when the system works, it's able to prevent harm to the country, and to our people.

Bill: All the systems worked. We had some ad hoc successes there. Not only did he have a viable UAM program on Mr. Hassan, but you had peer groups around him, and a supervisor identifying problems, as well. So, it was everything that should work, worked perfectly, and the Coast Guard has always been. They should be commended for having a viable inside threat hub, that merged those things together, to identify him, and prevent lives.

Bad Marketing

Bill: Then the government puts out paperwork every year about the number of suicides prevented, and the amount of employee work that's been interceded, to prevent harm to self or others. Where we fail at that is bad marketing. We just don't have a viable marketing capability to show why this stuff works. Specifically on monitoring employees' keyboard strokes, because they've been so successful. But we have to be more willing to declassify this stuff, not name people.

Show the success rate, where we're giving people the help they need when they need it.

Eric: What do you think works better, the detecting, or the preventing? I suspect you need both hand-in-hand.

Rachael: Well, I would imagine you would need both hand-in-hand. Coming back to your point about marketing, it's almost like insider threat becomes a bad word. Like we've got to whisper it when we talk about it, versus really looking at it holistically, I think is what we're talking about here. Because you can't prevent everything, but when you can detect something, and get ahead of it, then you could have a conversation, or you could do other things to mitigate it.

It's a hard problem to try to solve because there's just no easy answer. No matter what the path is, I think somebody's going to feel infringed.

Bill: I agree. To your point, my consideration to be in this space for two decades, detection is prevention. If you're not capable of detecting, you're not doing due diligence and preventing.

Eric: In research, I was looking at soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marine, and I guess guardians, now, suicide, harm to self, and harm to others came up a lot.

Annual Suicide Prevention

Eric: I was blown away. The government actually tracks, in a quarterly, and annual suicide prevention office, the defense suicide prevention office tracks. We had almost a hundred serving, 70 active duty in Q1, 18 reserve, and 20 national guard members that took their own lives in the quarter.

They track quarter after quarter, year over year, we're looking at almost 400 service members taking their own life every year. What are we doing about that? Just, these people sign up to serve this country. I feel this pain as a veteran, we haven't signed up to help them to protect them, to deal with the enhanced issues, challenges, and concerns they have. What are we doing?

Bill: I think it's horrible. I think those numbers are not all preventable, but if we can prevent one, it's worth every try. And I think we have an obligation. If you take the military service members who are raising their hand to protect this nation, we owe them every capability that we know. To be able to help them identify a person in need, so they can get the help. Secondarily, you multiply that times law enforcement, and the medical community right now, who are having still issues with COVID. We have the capabilities to prevent and identify those individuals who are in need.

And we should be held accountable if we're not doing it, and to me, it's a three-step process. For every one of those individuals, I want to go to their supervisor and say, "What did you see about this individual?" We have to train managers and supervisors. Then we have to hold them harmless. We cannot put them in a position to be afraid to report stuff, because they're worried about being sued.

[33:33] The Training to Identify an Insider Threat

Bill: So we have to give a little hold harmless, and give them the training to identify. Because if we just save one of those 400, or God forbid, 50 of them, which I think we can, then it's worth every effort to do so.

Eric: Who owns the problem?

Bill: The agency for which those individuals work. Because in the DOD ecosystem, and I don't want to beat up on DOD here, but they kind of deserve it. You have hundreds of insider threat programs. Each combatant command has its own program and its own principal leader. We have, in the insider threat program, there are three key areas. You got to have a senior leader, someone who owns the program, have training in a policy, and then you've got to have some capability to monitor something.

In DOD, every single part of the DOD is different. There's an analytical center that takes that disparate data in. But you might have a combatant command at PACOM that's lightyears ahead of where maybe someone is an after-command. As well as even inside the Pentagon, some services have better programs than others.

To me, all ships should be floating at the same level. We should put the same effort, and the same capability, and awareness into the insider threat program. Then also put the same tools that we have. Service A should not be using tools that are superior to Service B is, because their commander is a curmudgeon. He doesn't want to modernize or invade the privacy of their soldiers. That's nonsense. They shouldn't have the authority to do that.

Who Owns the Problem in DoD

Bill: I think that where DOD loses some ground, is the disparity which they are across the ecosystem. No organization can take the ball and move with it. Not without effort. In the last decade, don't get me wrong, there's been plenty of effort, but no one owns the program. No one owns the problem in DOD.

Eric: That is a recipe for failure in anything in life if you don't have a problem owner.

Bill: Well, if you're a PACOM commander, you own the problem in PACOM. Is that PACOM commander a senior leader of an insider threat? Do they know much about it? Who is their go-to? How do they get data from there to the DITMAC, which is in DOD analyzing the data? What data are going from there and what is that leader mandating women, and men, and under his command to report? Versus the commander in STRATCOM, or any other command. There's no consistency across the board for DOD. I think DCSA tries to drive some of those solutions, to get disparate data to the DITMAC. What I've seen over the last four or five years, is I think a problem that we're going to spend a decade dealing with. There's so much data now, that it becomes noise.

Eric: When you say DCSA, you're talking Defense, Counter Intelligence, and Security Agency.

Bill: That's correct.

Eric: So, it's centralized there. They do the security clearance paperwork.

Bill: They do security clearance. They do counter-intelligent advice and inform, informing of the clear defense contractors. And they own the DITMAC. They own the insider threat management analytics center.

The Gatekeepers From an Insider Threat

Bill: They’re the gatekeepers of the outcome of the data, but there's so much data coming in right now. I'm not sure we're capable of training enough people to identify what dials to turn up and turn down, what's hot, and what's not right. I think some agencies do that better than others, but we don't have a consistency of where that lies in the Defense Department.

Eric: As you said earlier in the conversation, they don't own the HR data. It's being collected, but it's not connected to anything.

Bill: Correct. To use our same scenario for all these points, you're doing your job effectively, you're working for a DOD element. In the last two years, you've applied for a promotion seven times, and you've got none of them. That should be at least an indicator of the security apparatuses.

Oftentimes you could apply for those jobs, and Rachel won't even know as a supervisor, that you've applied for those jobs. So, who knows? Just some little database in human resources. The only organization that knows that you have seven applications, of which you've got none of those jobs. That is a key indicator that somehow, we need to get that data. It is just a number.

It's a data point in security but is a viable one to say, "Okay, Eric might be susceptible to really being disenfranchised here in this organization. Let's compare that, put it with the rest of his profile, and see if we could identify an idea to go have a conversation with Eric."

Simple stuff.

Eric: It's so key, commercial, government. It matters.

A Programmatic Effort

Rachael: Bill, I'd love your perspective here. Do we as the employees, those of us who are okay with it, like I opt-in for you to check on me because, at the end of the day, it protects me as well? Let's say that you guys are tracking my keystrokes, and I don't know, somebody phished me or something like that. Then you've got a record of things as well. Is that a way to start moving forward a little bit or would anybody opt in?

Bill: It's a great honest question but the answer is no. It has to be a programmatic effort. In the government, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence has now what's called continuous evaluation. So, we got rid of the periodic reinvestigations, so you're being continually evaluated every month.

There are 3.9 million people in that system. It's an automated system that has red flags, and that says, "Okay, this is interesting." So that's phase A. It took eight years to get that process moving, from policy to the legal hoops, to multiple administrations. Then build the system to house it, and spit out the data to the disparate agencies.

That's the slowness and lethargic mindset of the government but it now works perfectly. But the end of that stream is, so we have key indicators on Eric that identify foreign travel, maybe reported, maybe not. He has had two police interventions in the last month, one at his home.

Eric: Down from last quarter.

Bill: We've had also a filing for bankruptcy, and then he has he's defaulted on two medical loans. That information goes from the ODNI to his home agency, for them to look at, and put a value on that.

Some Capability to Deal With an Insider Threat

Bill: We need to train those folks first, to be able to say, "Okay, what do we look at here? What is really viable? Then how do we go approach Eric?" That security individual can't be a retired Loudon County police chief. There has to be some capability there on that back end. In the private sector, what we're seeing now is, these stories, CEOs, and CFOs saying, "Let's get this, let's do it, make it happen. Do you want to work here? This is what we're going to do."

Then they put together robust training programs for every manager, what to look out for, and that you're going to be okay with having your keystrokes logged. You're going to only use our company cell phone. You are no longer allowed to use your private cell phone. So, some of my clients right now are moving fast and furious to this protective mode, saying, "Okay. We could fix this with money, some training, and someone who's responsible, let's do it." There's an aggressiveness. What the difference is, and honestly, they don't have to deal with unions and GS-14 attorneys who don't want to do this.

Eric: But they do have an office of general counsel who will caution, they will have the debates.

Bill: They do caution, but they say, "Yes, it's legal." Honestly, their general counsel asks me, "Benchmark us. Who else in our industry is doing this." If I don't have an NDA, I'll say, "Well, I can't tell you the name of the company, but four of your equals are doing the same thing." "Okay. We're good." They just don't want to be the outliers.

[38:31] Where There Needs to be Focus

Eric: So we've talked about marketing, we've talked about education. It sounds like there needs to be a focus on making it legally okay. \Getting legal involved, office of general counsel, again, to say, "Yes, we can do this." At the US government level, the Indo-PACOM commander is not going to have as much luck as somebody in the executive office would.

Bill: I also agree with you, but I think the general counsel who are for this and do this every day, we need to get them into a forum. Hypothetically, we're going to need to get the CIA, FBI, and NSA, to bring them together. Have a public forum to talk about the pros, and the benefits of having a subset of program, from a legal perspective, and educate.

For two years in a row, the US government, and the intelligence community legal forum, talked about this. We brought in all kinds of attorneys from the non-Title 50, so they can learn about the trials and tribulations that have already occurred legally for the last decade plus.

Let's not reinvent this wheel. I think we need to do more of that.

No, not only the chief financial officers, "How much does this cost?" But the general counsels, the privacy and civil liberty authorities, and lawyers, and I'll ask the security and the HR folks, all need to have their verticals in the discussion, as well as cross-conversation to understand this.

We have trained, and we built 2012, the Hub Training Course. It's basically, how do you provide an insider threat hub in your organization? Who needs to be in that? I've done that three times now in the private sector, I built them a very viable hub.

The Approval Process

Bill: The general counsels love it because they are co-chairs in their hub. If you put the general counsel as co-chair in the hub, there's immediate buy-in, because nothing gets beyond that.

Eric: Because they're part of the process.

Bill: They're part of the process. They're part of the approval process as well. I think that's the key, not to just be advice, and counsel, you are part of the approval process. My argument is if you have the general counsels not only buy in, but you make them a meat eater. If you make them a decision-maker, your program is going to be very successful.

Eric: Or put it in their wheelhouse. Like, “I want you to run the insider threat program."

Bill: I haven't seen that being successful because it's not in the writ. I think they'll say, "I'm just an attorney. And I want to advise and inform." But you could advise, and inform, and where I've seen, in my three clients right now, their general counsels are all deputy chairs of the insider threat hub.

Eric: So, in the classified world, we do a lot more, and we feel like we can intercede on an employee. I'm not going to use the word rights, but we can look at what they're doing on their computer. Today, we collect more information on what people are doing on their systems in the classified environment than we do in the unclass.

So, why do we do that? Why do we feel it's okay on classified, but not unclassified, both work systems, both in the same business, or organization, both under the same office of general counsel?

Where Do We Collect Insider Threat Data?

Eric: Why is one better than the other, and where would you have to, if you had to pick one, where would you rather collect?

Bill: I'll challenge your premise. I don't know if we, the Royal, believe that to be true. In my space, I believe both are true. We've been very successful collecting both, classified and unclassified. There is the discussion that's always been there in the Department of Defense ecosystem. But in the intelligence community, it's just as important, and successful on the unclassified side.

I will proffer to you that I know this for a fact. Since 2010 in this space, every IC organization will tell you, that all their big cases and their leads come from the unclassified side. The data is on the classified side, but the nefarious activities are always on the unclassified side. That's where we find the bad actors, and bad acting, is on the unclassified side, all the time. I would even throw in the unclassified side. The chat rooms that every agency has, are also in that space of what I would call the unclassified realm.

Eric: So one might actually say, the data, the meat, what we really want to get to is on the unclass side.

Bill: I would say that for sure, as a seasoned insider threat. The numbers and the data prove it to be true. What we identify, nefarious behavior on the unclassified, is always what leads us to the biggest, and best security violations, and counterintelligence cases.

Counterintelligence cases are oftentimes found on the unclassified side. The bigger picture though, at the end of the day, it's all about keystroking. It's all about your fingers on the keyboard.

The Bad Actor During an Insider Threat

Bill: So, if we're monitoring one, we should always be monitoring everything else. Psychologically, the bad actor thinks they're clear, when they request that button, they go to the unclassified, "I could type in anything online, and go to my home email. I can go on these chat groups, do my criminal behavior, and then click back to secure. Oh, I got to behave now." So, that's just a human mind.

Eric: First of all, that's bizarre to me, even thinking about on a government computer, or work computer, and looking up something that's even a hint risky. But, I'm with you.

Bill: Rachel's going to get offline, and find out who exactly would I report this to, anyway? Is there someone out there? And is there a portal to send us to? That's the first thing you're going to do.

Eric: Well, in this joint, that's true.

Bill: I think if you think about where you work, and I would ask you just rhetorically when I get off this, think about if you were to report one of your employees. How would you go about doing it? Even your company had that capability to do it, and what are the legal policy ramifications? Something to think through, that. I tell the private sector CEOs, "Think about what this looks like, feels like for the ground-level supervisor, the mid-level supervisor, and what are our expectations of those?"

And I will throw on, take everything we talked about here, which is really complex stuff, and then overlay it to where we are right now with the work-at-home concept. Where those individuals aren't being seen every day by the supervisors or their coworkers, and they're at home and they're oftentimes lonely.

Work-From-Home Mentality

Bill: They're having financial problems and that work-from-home mentality. Maybe now you can't monitor keystrokes at home. So, how do we take what we learn for a decade plus, and then overlay that to the new modern working environment ecosystem that we have? That's the future of where we are in insider threat, and I would say that is one of the biggest challenges we're going to have.

Eric: A lot of opportunities, but very scary.

Rachael: I'm glad we're having this conversation though. If we're not putting it out there, it's not going to have a broader conversation. It's never going to get figured out somehow. I'm really glad that there is an insider threat awareness month, because this is really important stuff, if you will, that we should absolutely be digging into, and making it a broader conversation.

Bill: I'll be out and about all month doing this all over the United States and in Europe. My argument to my friends and coworkers in the government is, please be judicious, and aggressive in sharing success stories. What I found out in the private sector if you tell company A the successes of other benchmark companies, they want to do that.

Then you also have the accountability to say, "Wait a minute, if we don't do this, how do we explain this to our board, that we had the capability to prevent it, and we didn't." I think that where the government needs to be more effective, and efficient is bragging about the successes of coming to the aid of employees that work for them. It is not just about preventing the Pensacola shooting or catching the next want-to-be spy.

[46:24] Providing Resources to Handle an Insider Threat

Bill: It's about providing resources to employees who have taken the oath, and are working for Uncle Sam, or the DOD ecosystem. It is providing them the help and assistance that we should be providing them because they are serving our country.

Rachael: That is important, the successes and the positive outcomes that can come from this. I don't think that's talked about really at all.

Bill: I'm trying to drive this a little bit more behind the scenes on the government contract relationships. There's a lot of awesomeness that goes on behind the scenes, but we're in this culture of secrets.

My argument is that if you don't want to share your successes, then why are we not? Don't give me this nonsense, there's a three-sentence rider on the contract on page 100. I don't want to hear that. We're obligated to share successes with other contractors. So, there are

4.1 million people in America that have a security clearance. Only 650,000 of them work for the government.

So, think about that. There are 1.2 million people that have a good way. 1.2 million people that have a top-secret, or higher clearance. A third of them don't work for the government. How are we not taking the successes we've learned, even from companies, and contractors, and sharing that with each other, to say, "We have successes?" Eric, you talked about that report you read from the government on suicides. What if we mandated contractors, and we made those same reports, what would those numbers be like?

Eric: They'd be higher. I have no idea. We've got to fix it though. That's one where you have to fix it.

Bigger Question

Bill: We do. That just goes to a bigger question for you folks in future podcasts on the acquisition, the Medieval times on acquisition contracts, and we have to modernize the way we do things. We build our contracts, and reporting requirements, especially when human lives and data are on the line. Again, not only just against our four nation states, but the workplace environment can be secure if we are willing to talk about the successes of keeping it secure and share those successes.

Rachael: That seems like a no-brainer to me, too. That's something that everyone wants to hear.

Bill: I think you should want to brag about all the good things that happen. Then other companies will be more in tune to say, "Wait a minute, why don't we have that? We don't have that? Why not?"

Eric: I'm still hung up on the numbers of intellectual property that our daughters, sons, wives, husbands, mothers, and fathers have spent so much time creating. It’s just flying out the door, which is causing harm to this country. That's a sad fact. I think we need some more awareness and some more action.

Bill: I concur 100%. We're all going to spend September talking about insider threat awareness and educating all the specifics of this. Not getting into the nitty gritty of the tools, capability, and identification of the UAM process. But why is it important to provide a service to our fellow employees that work around us every day, and are doing their best to make their company, or their government organization productive?

We owe it to those employees to provide them with the services they need. Sometimes when they're calling out for help, we need to be there and help them.

A More Positive Note

Eric: I couldn't end on a more positive note. That's what we've got to do.

Rachael: You've given folks a lot to think about, but it's important. It's really critical that this happened more often, and as broadly as possible, because that's the only way that change is ever going to happen. So, thank you for your time, and the many great insights you've provided here. It's been invaluable.

Bill: You're more than welcome, thanks for having me here. It's been a humbling opportunity and a great discussion. I enjoyed every minute of it.

Eric: Keep fighting the good fight. This country needs it.

Bill: We're on the same team. We're all working in the same boat, going in the same direction.

Rachael: Thank you to all of our listeners again for joining us this week. Don't forget, if you subscribe, you get episodes with amazing people like Bill Evanina, right to your email inbox on a Tuesday. You don't want to miss these. Until next time everybody, stay safe.

About Our Guest

Bill Evanina, Founder and CEO of the Evanina Group and former Director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center Office of the Director of National Intelligence, joins the podcast this week to take a deep dive view into insider threat as September is Insider Threat Awareness Month. He shares insights from his many years on the counterintelligence and security front lines on what defines insider threat (Note: harm to self or others), the opportunities and challenges in available tools, information sharing and detection across organizations, the importance of leadership training and cross-functional partnership to help mitigate insider threats and the criticality of sharing success stories (these really make a difference!).