Part 1 - The Ghost of Ransomware Past, Present and Yet to Come

0 Minuten Lesezeit

Ransomware: The modern way to extort money

When newscasters report yet another ransomware attack on a hospital, school, or high-profile enterprise, or that intellectual property or customer data has been publicly shared on the internet, we are no longer surprised. How did we end up in a position when ransomware attacks happen so frequently that it is not even really news at all? Ransomware did not appear by magic, so how and when did it become so ubiquitous? As with everything, there is a past to it.

Scare tactics

Before ransomware, there was another type of malware called FakeAV. As the name suggests, these were fake antivirus applications that could easily be found and downloaded for free by unsuspecting, conscientious users looking for reassurances that their machine had not somehow become compromised, usually because of some ill-advised browsing. But few things in life are free and upon performing a supposed scan of the system the users worst fears would be realized. The results would show numerous infections on the system, several of them with high severity, and that urgent action was needed immediately. Naturally, the newly installed software could remove everything that it found…just not for free.

These scare tactics sound simplistic and trivial to spot, yet they proved to be very effective, and FakeAV was extremely prevalent around 2010 just before the transition towards extortion-based campaigns started to gather pace. It could be argued that the very first strains of ransomware didn’t threaten to encrypt data, but continued the FakeAV trend of frightening users into parting with their money lest the fictitious malware would delete their data.

A similar tactic would see a message popping up on the desktop, containing logos of local or global law enforcement authorities, claiming that incriminating content had been found on the computer and a fine must be paid to prevent conviction. While the average law-abiding citizen would likely see straight through such a ploy, those of a more nervous disposition, or who had done anything remotely morally or legally reprehensible were very susceptible and would be more than willing to pay to rid themselves of the accusations. This only proved that the approach worked and warranted further exploration.

Digital hostages

Building upon these prior successes, cybercriminals went to work refining the strategy by considering how to increase the number of paying victims. It was clear that the threat would need to be more credible and, with that, the payment demands would have to increase accordingly. Personal documents such as family photos and videos could be easily identified as valuable content, so encrypting those files until a fee was paid seemed obvious. Modern ransomware was born. The very first encryption-based ransomware families, such as GPCode, are dated back to 2005, even though they’ve really become prominent only after 2010.

File or disk-based encryption can be done in a variety of ways, as such, the implementations in early ransomware were far from perfect. The custom algorithms, short keys, random number generators and libraries that were used all had their fair share of problems. As a result, the encryption could often be reversed by skilled security professionals.

Unfortunately, this was short lived, and the criminals quickly refined their approach to make decryption impossible. A sort of hybrid approach was employed where a quick symmetrical encryption algorithm (AES) was used to generate a key, which was then protected with a public/private-key solution (RSA) with a key size considered to be secure (1024+ bits). This resulted in a quick encryption process which was also secure enough to ensure that decryption was impossible without the necessary key.

Although the encryption was considered problem free, there remained some differences in the key generation process amongst the various ransomware families. One camp was generating both the symmetric and asymmetric keys on the target PC, meaning there was a need for an active internet connection to send the keys to a C2 server before they were wiped from memory (to prevent recovery by incident response teams). As this connection request could be detected by active security solutions, some of the more cautious actors took the extra step of generating new asymmetric keys with each new campaign. They built new binaries with the corresponding keys embedded. The former approach was more convenient for targeting home users, while the latter was more suited for corporates due to their multi-layered defenses.

First expansion phase - RaaS

Theoretically, operating a ransomware business has several challenges, such as maintaining the ransomware codebase, identifying suitable victims, developing enticing lures for successful infection, QA testing, distribution, and managing the extorted revenue. Along with the small matter of not getting caught. One would assume all this to be very time consuming. Like for many successful enterprises the solution was franchising. In the Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) model the developers could go back to doing what they did best, creating new ransomware variants, and the infection process was outsourced to different criminal entities who paid for access to the latest builds. This proved to be a success as there was no shortage of customers who would run email campaigns to propagate the ransomware—such as GandCrab—but wouldn’t be able to create malicious code on their own. RaaS kicked off sometimes in 2016 and it remains the model for most ransomware operations to this day.

Second expansion phase - EternalBlue

The NSA's cyber arsenal being leaked had its impact on the evolution of ransomware. Only a couple of months after Microsoft issued a patch for the EternalBlue exploit, WannaCry emerged and shocked the world. Due to its extraordinary impact, it did not take long for other ransomware groups to follow suit, which ultimately lead to a much wider penetration rate compared to ransomware attacks in the past. Armed with this new exploit, cybercriminals became capable of infecting the infrastructure of complete enterprises at once, and they knew it, so the price of the ransom increased equally.

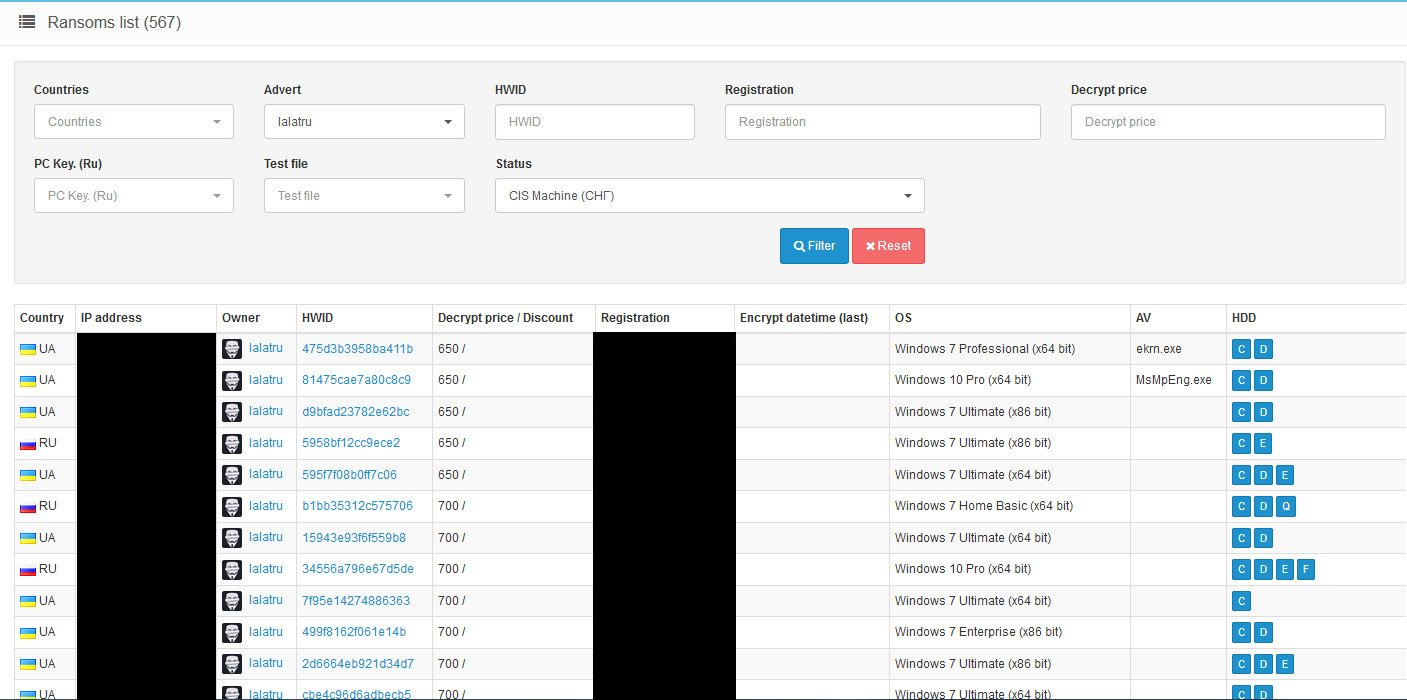

Third expansion phase - Affiliate programs

Nothing lasts forever and Server Message Block (SMB) exploits are no exception either. Once companies were patched against the use of EternalBlue, the ransomware gangs had the same old problem of finding new ways to infect victims at scale. This time the answer wasn’t technological, but organizational. They expanded further on the RaaS idea and were on the lookout for cybercriminals with complementary skillsets. Teaming up brought skills to the table beyond running email campaigns, as they could now successfully attack organizations of any size or kind. Also, now rather than selling the latest ransomware code for a fixed price, their partners would take care of the execution of the attacks and in return took a percentage cut of the ransom once the victim paid it - usually between 10-30%. This new arrangement also provided a certain degree of separation between the ransomware creators and the ones perpetrating the actual attacks. This didn’t make them untouchable, but it did reduce their risk of getting caught.

Similarities and differences between groups

Not every ransomware group has the same technical capabilities and TTPs (Tactics, Techniques and Procedures), however there are certain key commonalities which have appeared over time. The days of weak crypto are long gone, and most of the modern ransomware families now utilize a common scheme which consists of a fast symmetric encryption algorithm whose key is protected by a secure asymmetric one. This ensures that once shadow copies are deleted and content is encrypted, no files can be restored within a reasonable time frame without the right key.

Also gone is the use of C2 servers for key storage. With the advent of mass infection, it became unnecessary to risk detection by generating keys in the target environment and transferring them back to the attacker’s server.

Another common feature is the almost exclusive targeting of Windows. There have been exceptions in the form of ransomware for Linux based platform (i.e. for specific NAS devices or Android), but the go-to platform remained one from the Redmond giant’s portfolio.

Finally, most actors were switching from the traditional shotgun-like distribution to post-compromise attacks. Instead of launching opportunistic attacks against a wide range of targets they are now attempting to gain privileged access to the victim’s infrastructure. Most of the time that equates to the impersonation of a domain administrator. The initial access to the network is either achieved with the help of additional malware—such as Trickbot—or by hacking their way in.

So, what about the differences? What makes one ransomware group markedly different from the others? Forcepoint X-Labs have been keeping a close eye on some of the more successful ransomware families to better understand their inner workings. In Part 2, we'll cover them to understand their unique characteristics, the targets they choose and how they attempt to evade detection.

- Forcepoint Advanced Classification Engine (ACE)

In dem Artikel

- Forcepoint Advanced Classification Engine (ACE)Lösungsübersicht lesen

X-Labs

Get insight, analysis & news straight to your inbox

Auf den Punkt

Cybersicherheit

Ein Podcast, der die neuesten Trends und Themen in der Welt der Cybersicherheit behandelt

Jetzt anhören